Glass has become one of the defining materials of contemporary architecture. From landmark towers in North America to energy efficient housing in Europe and rapidly growing cities across Asia, transparent facades represent progress, daylight, and sustainability. Yet for birds, these same surfaces are among the deadliest and most preventable human made hazards. Across the world, collisions with building facades are killing hundreds of millions of birds every year. This is not a local problem or a niche conservation concern. It is a global design challenge that sits squarely within the responsibility of the building industry.

By Jatin Sanjay Gupta, MSc Lund University, Sweden – February 2026

Global crisis hidden in plain sight

Current scientific estimates suggest that bird collisions with glass account for close to a billion deaths annually in North America alone. Europe follows with tens to hundreds of millions of fatalities each year in countries such as Germany, Sweden and Poland. In many parts of Asia, Africa, and South America, reliable data is still limited, yet rapid urbanisation and the widespread adoption of glass heavy construction strongly indicate that the true global toll is far higher than existing figures suggest.

Bird collisions with buildings now rank among the leading sources of human related avian mortality, comparable to domestic cats, power lines, and road traffic. Unlike many other drivers of biodiversity loss, however, this threat is highly preventable. The tragedy lies not only in the scale of loss, but in the fact that well tested design solutions already exist and remain rarely used.

A small but growing number of cities have begun to translate this knowledge into regulation. Toronto became the first municipality in North America to require bird friendly standards through the Toronto Green Standard. In the United States, cities such as San Francisco, New York City, Madison, and Washington DC now mandate bird safe glazing in the most collision prone facade zones. At a broader scale, the European Union Birds Directive establishes a legal obligation to avoid the killing of wild birds, a requirement increasingly interpreted to include hazards created by large, glazed facades. Voluntary but influential systems such as the LEED rating framework have also helped push bird collision deterrence into projects worldwide, even in the absence of local regulation.

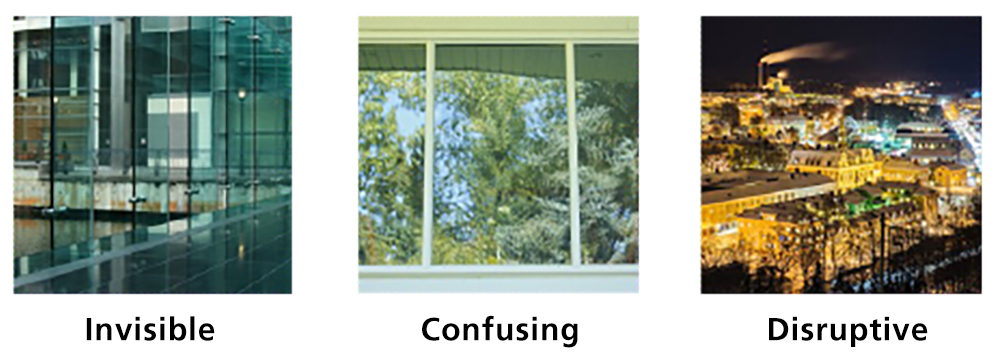

Birds do not perceive glass as humans do. Clear glazing appears invisible, while reflective surfaces mirror sky, vegetation, and water, creating the illusion of open habitat. Transparent corners, glass bridges, balustrades, noise barriers, and bus shelters further reinforce this deception, encouraging birds to fly into spaces that do not exist.

This risk is amplified by avian vision. Many bird species can perceive ultraviolet light and rely heavily on peripheral vision during flight rather than forward focus. Collisions occur for two primary reasons. Reflection causes birds to mistake mirrored trees or sky for real habitat, while transparency leads them to attempt to fly through glass they cannot perceive. The presence of vegetation, particularly trees, near windows is consistently linked to increased collision risk. Trees attract birds for refuge and food, and their reflection in glass makes the barrier less visible. Literatures indicate that even single trees close to buildings can increase reported collisions. Lighting conditions, seasonal migration patterns, building height, and proximity to vegetation all influence collision risk. The result is often highspeed head-on impact, leading to severe internal injuries or instant death.

Energy efficiency and unintended consequences

The drive to lower operational energy use has quietly reshaped facade design. Bigger areas of glass, thicker glazing units, and increasingly sophisticated coatings now show up in projects almost by default. From a climate perspective, these choices make sense. Still, they seem to come with side effects that are easy to miss. When biodiversity is not part of the discussion, certain facade features start to work against wildlife. Highly reflective surfaces, barely visible framing, and smooth, uninterrupted glass can become serious hazards for birds, especially in everyday urban settings rather than just iconic towers. What performs well on paper does not always behave the same way once birds enter the picture. Importantly, bird collisions are not limited to tall buildings. Low rise residential buildings and private homes collectively account for a significant share of global mortality simply because of their sheer number. As glass becomes more prevalent in everyday construction, the risk expands across all building typologies.

Worldwide governance gap

Building laws still hardly ever incorporate bird-safe design, despite decades of scientific proof to the contrary. Incentives or regulations for bird-friendly facades have only been implemented in a few cities and areas, mostly in the US and Canada. Unfortunately, implementation is either completely non-existent, inconsistent, or voluntary across the majority of world. A larger gap between biodiversity targets and the built environment is reflected in this regulatory gap. Global sustainability frameworks place a strong emphasis on resource efficiency and climate mitigation, but they hardly ever address wildlife mortality associated with buildings. Because of this, energy, structure, and aesthetics are frequently used to gauge facade performance, but impact on biodiversity is frequently disregarded.

Solutions already within reach

The good news is the fact that there is a way to avoid this disaster. As per multiple research efforts and field tests, making glass visible to birds can prevent collisions by more than half. Patterned and fritted glazing, ultraviolet reflecting coatings and interlayers, external films or etched patterns placed to the exterior glass surface, and architectural features like screens, fins, and shading devices that break up reflections are examples of effective techniques.

Crucially, the spacing and placement of visual markers matters more than the amount of glass covered. Recommendations from conservation groups and industry experts converge on the need for dense patterns: maximum spacing of five centimetres between elements is a key guideline. Industry experts specify patterns should be at least 6 mm in diameter and spacing at least 3 mm horizontally, 5 mm vertically, and 9 mm diagonally to be effective. Patterns should ideally be placed on the outside surface of the glass to counteract reflections.

Fritted glass uses ceramic patterns baked into the surface of the glass, making the facade readable to birds while remaining visually subtle for people. Bird friendly lighting further reduces risk by limiting unnecessary nighttime illumination, shielding interior lights, and using warmer colour temperatures that are less disorienting during migration. When integrated early in the design process, bird friendly facades do not compromise daylight, views, or energy performance. On the contrary, many solutions improve glare control, visual comfort, and solar shading. Bird safety can therefore align with high performance facade design rather than compete with it.

It is impossible to isolate facade design from its surroundings. The risk of collisions is greatly increased by vegetation right in front of windows, reflective water features, and poorly located bird feeders. In metropolitan regions where glass risks are prevalent, migratory birds are drawn to artificial light at night, especially from glazed atria and prominent structures. The best mitigation techniques used worldwide combine smart landscape planning, responsible lighting design, and bird-safe facades. It is rarely adequate to address one factor alone.

Objective assessment systems already exist to evaluate bird collision risk. The American Bird Conservancy (ABC) has developed a Threat Factor (TF) rating that scores materials based on how visible they are to birds under controlled testing. In Europe, the Biologische Station Hohenau Ringelsdorf in Austria conducts tunnel tests to evaluate product effectiveness, rating them based on collision rates or deterrence scores. These systems provide designers and manufacturers with comparable, scientific tools for selecting safer facade materials.

A call to the global facade industry

The facade industry is crucial in determining this result. Bird safety must be acknowledged as a fundamental design obligation for architects, facade engineers, manufacturers, developers, and legislators to significantly lower bird fatality. It should be given the same consideration as structural integrity, fire safety, and thermal performance. In the same way that energy efficiency revolutionized facade engineering in the last few decades, biodiversity conservation now needs to be integrated into everyday operations.

Millions of avoidable deaths occur each year because of delays. There is shared accountability, the science is evident, and the solutions are validated. The question is no longer whether we can create bird-safe facades, instead whether we want to, as glass continues to dominate the cities of the future. Preventing the deaths of birds that bring life, beauty, and balance to our world from something as simple as glass is within reach. By rethinking how we design and live with our buildings, we can ensure that our skies remain full of birdsong and not silence.

Case studies

Oregon Zoo Education Center, Portland, USA

Architect: Opsis Architecture

Fabricator: Oldcastle

Sustainability Design Lead: Heather DeGrella

The Oregon Zoo consistently attracts more than 1.6 million visitors per year and has more than 42,000 member households, giving it a unique platform for broad-based community education. Honoured with multiple awards, the Education Centre educates the public on how to live sustainably with natural systems and habitats for the health of life. Built with Forest Stewardship Council-certified wood, the Education Centre includes a wide variety of sustainable design features, including an extensive rooftop solar array, rain gardens that capture and clean stormwater before releasing it to the Willamette River or providing it for use in nearby restrooms, energy-efficient lighting and HVAC systems, radiant floor heating, and bird-friendly lighting and fritted glass windows. Throughout the Centre, Opsis Architecture used AviProtek® E bird friendly glass in pattern 211. A low-e coating on the second surface of the glass minimizes energy waste and helped the project achieve LEED Platinum status.

Jacob K. Javits Convention Centre, New York, USA

Architect: I. M. Pei Cobb Freed and Partners

Renovation Architect (2010-2014): FXCollaborative

Structural design: Thornton Tomasetti

CM: AECOM Tishman

The Jacob K. Javits Convention Centre was once a major site for bird collisions, but a 2014 renovation that installed bird-friendly glass has since reduced bird deaths by over 90 %. Studies by the NYC Bird Alliance’s Project Safe Flight found that the building was responsible for the deaths of thousands of birds annually before the renovations. The reflective, mirror-like facade led to the building being nicknamed the “Death Star” due to the high number of bird strikes.

As part of half a billion-dollar renovation, approximately 6,000 panes of the original glass were replaced with fritted glass. This glass has a ceramic dot pattern that is barely visible to humans but easily seen by birds, helping them to perceive the glass as a solid barrier. The renovation also included the installation of a 6.75-acre green roof, which has transformed the building into a wildlife sanctuary and stopover habitat for over 70 species of birds and five species of bats. The Javits Centre’s success story was a key case study used to advocate for New York City’s Local Law 15, which now requires bird-friendly materials on most new constructions and major alterations.

Useful links

Glass/Window Used in Oregon Zoo Education Centre

Jacob K. Javits Convention Centre

Personal Thesis on ‘Bird collisions with buildings in Sweden’

the Biologische Station Hohenau Ringelsdorf

Natural History Musuem (Naturhistoriska riksmuseet), Stockholm

Personal LinkedIn profile Jatin Gupta